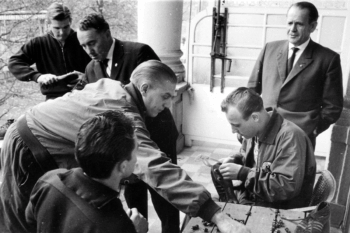

In the nineteen sixties, adidas numbered 550 employees and was the world’s largest producer of sport shoes. By the end of the decade, the brand with the three stripes operated 16 factories and produced 22,000 pair of shoes per day. Nevertheless, Adi Dassler remained modest. He never sought the spotlight and seldom gave interviews. He was more interested in tinkering with new inventions, developing new ideas and putting them to practical use. Throughout this creative process, he approached his work in a precise, earnest, structured and always creative manner. Over the years, he registered hundreds of patents to protect against competitors, Puma being one them. His best-known innovations: the continuous improvement of the screw-in cleats for football shoes, replaceable spikes for track athletes and the use of nylon soles to drastically reduce weight. Adi devoted himself not only to the functionality of the shoe, but also to weight reduction. From the beginning, pliability and light weight distinguished his shoes from those offered by the competition. To achieve these design goals, Adi promoted the development of thin, strong, lightweight leather and suppliers made every effort to meet his demand. The weight of the newer models was cut in half with each shoe tipping the scale at only 140 grams. However, more than just the rewards of technical innovation drove his ambition. The subsequent success of “his athletes”, with whom he felt a strong bond, was to Adi both affirmation of his philosophy and a source of further motivation.

By the beginning of the decade, Adi had begun developing cutting edge sport shoes in close coordination with orthopaedic doctors and sports medicine specialists which led to specialized shoes for injured football players and track athletes. Uwe Seeler’s customized football shoe, with padding and additional laces in the heel, is the most notable example. Without this special shoe, which he wore during the legendary game against England at Wembley Stadium, he would not have been able to play due to an injured Achilles tendon. With this special shoe, Adi prevented Seeler’s premature departure from the game.

Adi Dassler also received recognition outside the field of sports as evidenced by the bestowment of two special honorary awards. In 1968 he received the “Bundesverdienstkreuz Erster Klasse” (German Order of Merit, First Class) and in 1974 the state of Bavaria recognized him with the Bayrischen Verdienstorden (Bavarian Order of Merit).

A unique challenge: Shortly before the Olympic Games in Mexico 1968, cinder tracks were replaced with rubberized, manmade material. In dry conditions, the surface was rough but when wet, the track was slippery. Contemporary long track spikes were no longer suitable because they penetrated too deeply and remained lodged in the new surface. Adi’s business competitors sought to address the problem by constructing shoes with a multitude of fine needles (Brush Shoes) but the Olympic Committee banned this type of shoe due to the increased chance of injury to the athletes. Adi chose a different technique and developed the blunted triangular element (spike) that didn’t get stuck in the plastic track and noticeably reduced strain on the athletes’ Achilles tendon. The resulting number of medallions won at the Olympic Games 1972 in Munich, the large majority of which were obtained by runners, spoke for itself: 80 percent of medals awarded went to track athletes wearing adidas shoes.

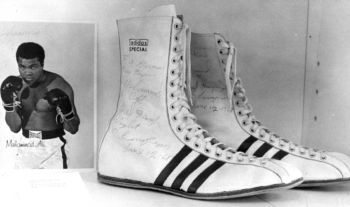

In 1971 Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier both wore adidas boxing shoes when they met at Madison Square Garden in New York to engage in the “Fight of the Century” and in 1972 the American tennis player Stan Smith won Wimbledon in shoes from Adi Dassler. Decades later, that same tennis shoe was recreated as part of the legendary “Originals” line of shoes and became one of the world’s most popular leisure time shoes.

In the 1970’s as sports became ever more professional and more money came into play, Adi had little tolerance for athletes who chose their sporting goods outfitter based solely on who paid the most. Throughout his life, he had only one wish: That athletes choose to wear his shoes because they were the best on the market and would carry them to the greatest success. The trust of the athletes in Adi’s innovative spirit showed itself outside the world of competitive sport. In 1963, several athletes asked if he could produce a practical shoe they could wear in the locker room or, better yet, even in the shower. Adi Dassler responded and the result was the Adilette (rubberized modern form of sandal). Although it occurred to no one at the time, this adidas product not only became a best seller but also achieved cult status and continues to be worn by regular people for everyday use.

In 1967 he produced the first track and field warmup suit, emblazoned with the iconic three stripes, so athletes could wear functional clothing before and after events. With this move he intuitively laid the groundwork for the expansion of sportswear into the leisurewear market and simultaneously achieved a significant increase in public exposure to his trademark.

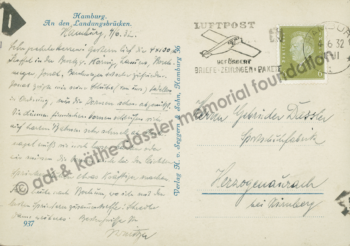

Unfortunately, the decade of the seventies was marked by more than positive developments. Adi endured personal loss as he became the last surviving family member of his generation. On October 27, 1974, Adi’s brother Rudolf passed away followed in December 1975 by the oldest brother Fritz. Maria, the only sister to the Dassler brothers, had already died in July 1958 at the age of 64.